Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

Natural project risk management

by Matthew Leitch, first published 15 October 2003.

Contents |

Time to make project risk management work

Think of famous failed projects. If you live in the UK like me the first that come to mind are probably government projects because they get a lot of publicity. Did they have project risk management in operation? Of course. Did it work? Obviously not.

The Unexpected is a powerful force but formal risk management tends to end up as a feeble, muddled attempt to secure a project that is being done in a highly risky way. The bureaucracy of risk registers and workshops can be costly yet ineffective.

Solving these problems involves two things: (1) using more powerful risk mitigation actions, of which Evolutionary delivery and its like are the leading examples, and (2) using more rapid and effective methods for devising and revising the total risk management scheme for a project, pulling in the powerful risk mitigation actions where they are needed.

This paper concentrates on the second part of the solution: a rapid design process for devising the full risk management scheme for a project, though it includes a list of potential actions.

The techniques proposed are based on my work in designing internal control systems for large scale business processes and systems. The techniques that work well and save much time in that work could be applied to project risk management.

6 principles for doing it faster

Six powerful principles can be combined:

Start with a generic scheme of actions in mind, not a blank sheet of paper. The idea is to decide how to adjust the emphasis and choose between alternative techniques given the specifics of a project. This makes it easier to think of actions and create a comprehensive scheme. The generic scheme may well reflect the industry or type of project, making it even easier to tailor quickly.

Pack the generic scheme with powerful, varied actions. An effective scheme will include many different actions, based on many different ways of thinking about risk and uncertainty. Do not imagine that listing ‘risks’ and then trying to think of actions to put against each one is all you need.

Reason from observations about the distinctive characteristics of the project. ‘Distinctive’ things are of course those that are most likely to require tailoring of the generic scheme. This saves the trouble of considering factors that have little or no impact.

Reason directly from distinctive characteristics to actions, where you can, but otherwise to deductions about the actions.

Think first about ‘areas of uncertainty’ rather than specific risks. Avoid getting sucked into detail you don't need and keep upside risks in mind as well as downside ones.

Achieve rigour by iterations. Repeating the analysis allows you to go deeper and adapt to new information.

The next sections explain these in more detail.

Generic schemes as a head start

Starting with a generic scheme and using analysis to tailor it to a particular project at a particular moment has many advantages:

It is natural. This is more like what happens in the mind of an expert, but if you have it on paper too it makes it easier for those who are less expert.

It saves time. One of the hardest parts of conventional risk management workshops is thinking of worthwhile actions. Having a list of good candidates there in front of you makes it much easier.

It can anchor expectations at a higher level. ‘Anchoring’ is a psychological term that refers to our tendency to stay near the first suggestion made. (This happens even when we know the first suggestion was made at random.) If your generic scheme is a strong one it helps anchor people around strong risk management. This is not a trick. People have a tendency to underestimate the impact of their uncertainties and be over-confident generally, so encouraging them to plan more aggressive risk management actions helps counter this. This means your generic scheme has to be a strong one, otherwise you could get the opposite effect.

It puts ideas on the table that otherwise might not be thought of. Even an expert can forget a technique that might be relevant, so having the list is helpful to everyone.

It's a safety net if your tailoring is poorly done. A well tailored scheme is better than one that has not been tailored, and better than one that has been tailored badly. However, un-tailored and badly tailored schemes based on a sound generic scheme will tend to be better than something based on nothing much at all. In the extreme case of no tailoring at all at least you have a scheme of risk management to work to, even if it is not efficient. There is less of a risk of missing out something important.

It is a basis for learning from similar projects. Rather than a totally generic scheme you can use one that reflects typical needs and techniques for the sort of projects your organisation/department typically does. Alternatively, your generic starting point could be a scheme laid down by a regulator, or by some organisation's ‘best practice’ guidelines.

There is no one generic scheme that is essential to make this approach work. Almost anything will do, but obviously some schemes are better than others. Ideal schemes have the following characteristics:

The risk management actions are grouped in a helpful way. For example, into actions that achieve the same thing, or are different levels of intensity for the same job.

The actions or groups of actions are organised into a system, so that it is easier to see how they work together. Often this makes it easier to see how strengthening one type of action compensates for weakness in another.

The risk management actions are organised to be memorable. That usually means they form a logical breakdown. It means you can easily explain the options, in a structured way, from memory.

It incorporates powerful actions that can really make a big difference, such as Evolutionary delivery.

The items in it are easily translated into specific actions. For example, a motto like ‘transfer, avoid, treat,...’ is not suitable on its own because most people have to think too long to come up with something specific for each one. These could be headings for groups of more specific actions such as ‘put risk sharing terms in a supplier contract e.g. using one of the following techniques ...’

Where relevant, it is consistent with, or based on, some recognised framework. For example, for demonstrating compliance with section 404 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act 2002, where the Securities Exchange Commission rules say you must use a recognised framework for evaluating your controls, and that means it may be more convenient to use it in design too.

Although it is obvious that an abstract scheme is not helpful enough it is not clear how much detail is ideal. In the related field of designing internal control systems for financial processes I have seen some attempts to provide a very detailed generic scheme, usually involving a database of controls from which the designer selects. While I can see no objection in principle to this they have been disappointing in practice, with the wording of specific controls being too vague to be helpful or credible.

Suggested generic scheme of risk responses

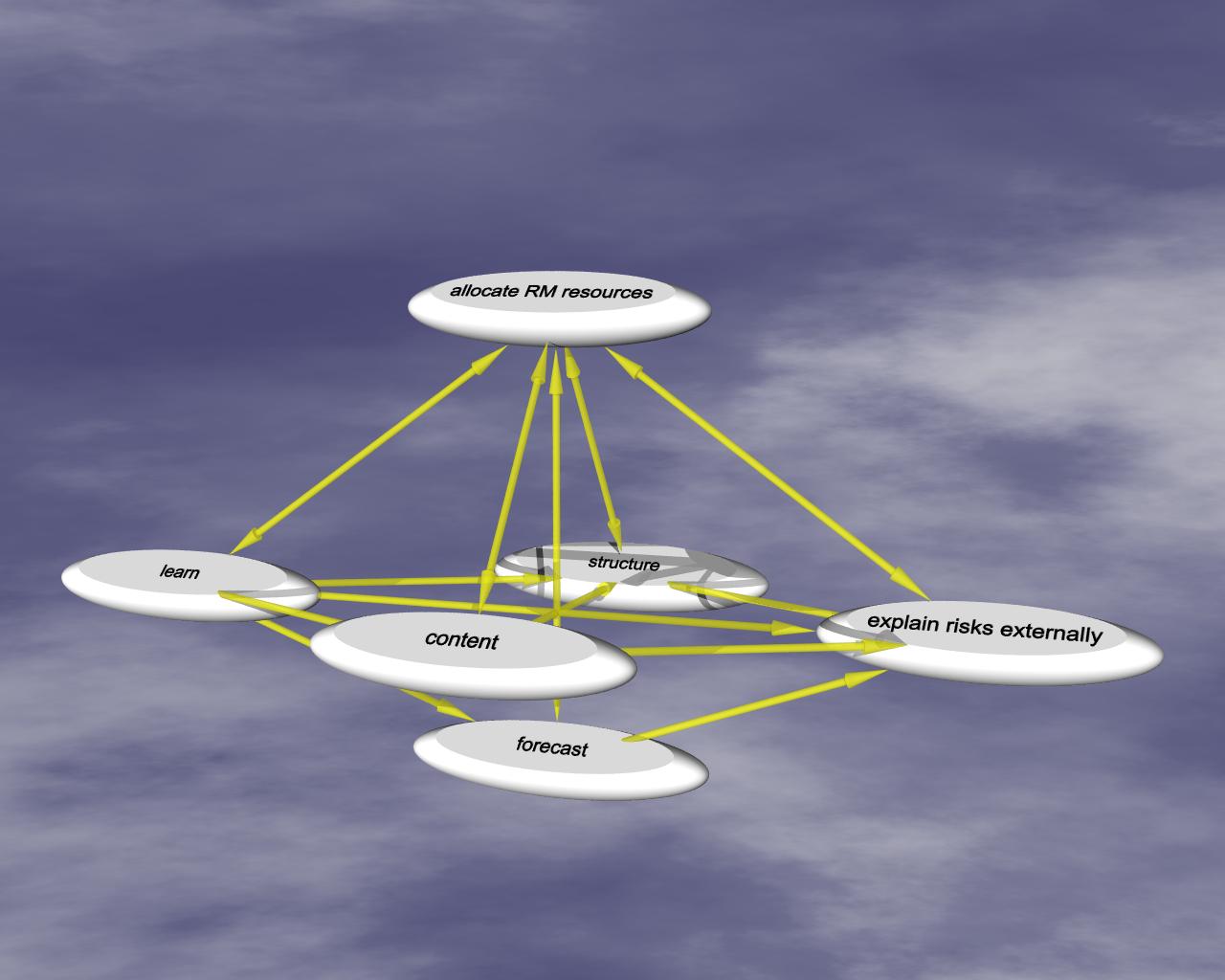

Many different schemes could be a good basis but here's one I like that is broad and meets most of the criteria set out above. Responses are divided into 6 types and these form a system. Within each type there are various alternative techniques and another way you can tailor the scheme is by deciding where to place your emphasis, building up from no focus through broad decisions about emphasis, then adding more specific points of interest. To begin with, here's a picture of the 6 elements of the system:

At the top, directing resources/attention is ‘allocate RM resources’, which is what this paper is largely about. It takes information from learning and other activities and decides where to put the risk management effort. That risk management effort goes into learning, into structuring the plans to control risks, into changing the content of plans to control risk, and into forecasting risk and communicating it externally to stakeholders. Obviously this is to be a continuous, or at least frequent, activity that should start as soon as possible.

There is no need to wait to start thinking about how to allocate risk management resources. Don't wait for an agreed scope or any of that paperwork. As soon as you have some scraps of rumours about the project that is enough to begin making deductions about how to cope.

Within each of the six activities emphasis can be placed in various ways. By default, your approach will be fairly general with few if any specific points of focus. However, more analysis will allow tighter focus of resources on more specific areas or even particular outcomes, layered on top of a safety net of general risk management procedures. Dimensions along which you might choose to focus resources include:

Phase of the project. (For projects done using Evolutionary deliveries this means concentrating on particular deliveries or groups of deliveries.)

Internal versus external to the project. Some projects have to be done in a very hostile or opportunity rich external environment, while the success of others is more dependent on competence, organisation, and honesty in the project team. These demand an external and internal focus respectively.

Upside versus downside. In the past risk management has nearly always concentrated on downside risks i.e. things that could go wrong. This is changing as it is gradually recognised that a more balanced approach within one management system is more effective and efficient.

Responses versus meta-responses. A risk response might be to do some market research. A meta-response might be to get better at doing market research.

Stakeholders. Different stakeholders may have different needs for risk information.

Typical specific responses and techniques in each of the six groups are as follows:

- Allocate risk management resources

- Rapid risk management planning method

- Risk identification → response planning

- Analysis by examining each project step

- Analysis by stakeholder/value driver/objective

- Causal modelling, fault tree analysis/dependency analysis

- Analysis of risk factors

- Educating project team to be open about risk and uncertainty and manage it explicitly

- Learn

- Acquiring expertise

- Training

- Recruitment

- Tracking of generic risk factor trends

- Ongoing monitoring of specific areas of uncertainty

- External horizon scanning, including

- Repeated discussions with stakeholders

- Monitoring other sources of news about the circumstances of stakeholders...

- ...and other factors that affect the project

- Internal horizon scanning, including looking for signs of weakness and growing issues

- Clarifying requirements and objectives

- Research

- Prototyping

- Structure plans using inherently risk-smart patterns

- Incremental delivery

- Evolutionary delivery i.e. ideally around 50 deliveries of real benefits to at least some stakeholders, with rethinking at each delivery. Massive risk reduction effect even with fewer such deliveries

- Portfolio of activities i.e. in parallel and success of each is largely independent of the others, though it may be correlated. Similar to Evolutionary, but in parallel. In general it helps to reduce dependencies

- Redundancy – multiple chances to achieve something.

- Real options i.e. giving yourself more choices in future by keeping options open and creating new options. Could be as simple as having some contingency in the schedule or cost estimate

- Critical Chain buffering

- Put all ‘padding’ into an overall project buffer

- Put feed buffers in front of activities on the critical chain

- Do project steps early that will give information that reduces uncertainty

- Content changes to manage risk

- Routing

- Away from downside risks

- Just don't do the thing with too much downside risk

- Also do something else e.g. choose less innovative technology

- Towards upside risks

- Just don't do the thing with not enough upside risk

- Also do something else

- Modify causes

- Reduce/enhance causes

- Reduce or increase the level of a driver somewhere in the causal chain leading up to the outcome you are concerned with

- Break or strengthen a link in the causal chain

- Add new causes

- Modify impacts

- Reduce/enhance impacts

- Pick up impacts very quickly and limit their effect e.g. inspection of documents through all project stages as in Gilb's Defect Detection Process.

- Make a contingency plan. i.e. just think about what you would do

- Have resources for the contingency, or otherwise create an option in advance

- Specific to identified risks

- Generally for unidentified risks

- Exchange risk with contractors or JV partners or employees

- Contract with contractor

- Fixed price contract

- Risk-reward and risk-sharing contracts

- Target cost incentivisation

- Specific risks (included or excluded)

- Liquidated damages

- Incentive/penalty payments

- Contracts with JV partners

- Reduce total involvement

- Avoid downside risks

- Retain upside risks

- Add new impacts

- Insurance and similar

- Insurance

- Self insurance

- Captives (owned or rented)

- Performance bonds, warranties, guarantees

- Forecasting

- Subjective estimates by experts

- Monte Carlo simulation – easier than it sounds

- Model future decisions within your Monte Carlo simulation

- Bayesian Model Averaging to deal with model uncertainty

- Communicate risk externally

- Probability distribution(s) for future outcomes

- Explanation of specific areas of residual uncertainty.

A number of things in this suggested scheme need additional explanation.

The list of techniques may look long, but it is still far from complete. If possible a scheme more specifically tailored to the type of project an organisation typically does should be used instead of a totally generic scheme. For example, if your organisation does civil engineering projects then a scheme that lists the things often done on such projects will be more useful. Devising such schemes is part of embedding risk management.

The output of rapid risk management planning as described in this paper is a mixture of specific responses and decisions to do more risk management analysis. In practice it is often hard to draw a clear distinction, and not important to do so. What is important is to direct attention appropriately, and that can be done by gradually working down to more and more detail, but only where it is worthwhile.

Risks should usually be met by multiple controls, and controls should usually meet multiple risks. In other words, the control scheme should be multi-layered. For example, you may take actions to make some bad event less likely to occur, and also plan for the contingency should prevention fail.

In the suggested scheme above I have not made it clear which actions are alternatives and which should be used together. Typically you should build a multi-layered control system so the individual controls accumulate. How much depends on how much emphasis you need. However, some controls are incompatible and cannot be used together.

This breakdown uses the preventive vs contingency distinction rather than the probability vs impact distinction. (It's in the section on modifying content.) These distinctions are very similar in practice but I suggest thinking about cause and effect because it refers more directly to what you have to think to find risk responses.

A single possible event can have both positive and negative effects, even from the point of view of one person. Look for ways to make events that are, overall, unhelpful less likely, and events that are, overall, helpful more likely. This may not be obvious as it is the net impact after possible modifications of the impact that matters.

Certain activities tend to merge in practice. Learning and allocating risk management resources tend to be very close and often done in the same activity. Learning and forecasting are also very close. Communicating risk externally to stakeholders and hearing their news is often done in the same meeting.

The value of continuing with a project should be reviewed from time to time, but I have not included this under risk management activities. Some other approaches do.

Reasoning rapidly

There are many factors that might be worth looking at when designing a risk management approach for a project. In the late 1990s the accounting firm Coopers & Lybrand offered to review project risks using a ‘tool’ called SQA 2000. This was in fact a questionnaire with thousands of questions on it. Very thorough but how often do you suppose all the questions were relevant?

Factors about a project that are most worth finding out and considering are those that (a) are often relevant to the way risk and uncertainty should be managed, and (b) are distinctive of that project (i.e. meaning that it is different from the assumptions underlying a generic scheme).

Factors commonly relevant to risk management decisions include:

- Control performance requirements

- Fixed-ness of the end date.

- Fixed-ness of other resource limitations.

- Sensitivity of project benefits to the quality of the deliverable in the desired range.

- Total money and other resources involved.

- Sensitivity towards resources used, especially perceived over-runs

- Project features

- Construction project vs ‘change’ project with wider scope.

- Exposure to external uncertainties.

- Degree of new problem solving needed.

- Whether or not you've done a similar project before.

- Whether or not you will do another similar project later.

- Length of the project.

- Size of the project.

- Ease of slicing the project into evolutionary steps.

- Nature of content e.g. building, research, software.

- Need for special skills for crucial steps.

- Variability of project workload.

- Number of major contractors.

- Dependency on contractors.

- Scope for sharing risk with contractors.

- Number of locations where the project activities are to be done.

- Complexity of dependencies, especially those that seem unavoidable.

- Cultural features

- Company culture of uncertainty suppression.

- Company culture in relation to giving people a second chance and taking circumstances into account.

- Industry practices.

- Rivalries between consultants/contractors on the project.

- Number of national cultures.

- Political opposition.

- Environmental features

- Whether or not the business case is based on unpredictable demand.

- Rate of change in the organisation generally.

- Rate of change in its industry/sector.

Consider each factor and see what it suggests, individually and in combination with other factors. Distinctive characteristics may suggest conclusions about:

Risk management actions that are appropriate, not appropriate, important, or not important. If the logic is clear and compelling these are the best inferences as they cut through any intermediate analysis.

Areas of uncertainty. These are effectively collections of upside and downside risks. If you cannot make an inference about actions directly you can often do so indirectly from a conclusion about an uncertainty.

Resources. Some conditions make certain actions cost effective and rule out others. This is not a matter of risk, but usually of simple economics. Sometimes some actions require skills that are not available, so compensation somewhere else is needed.

Time. Like economics, shortage of time can rule out certain risk management actions and make others more suitable.

Cultural fit. Some companies, professions, projects, even individual personalities have a certain style that makes some risk management actions appropriate and some not. This should not be an excuse for doing nothing about risks that really should be managed. It just means that risk management may have to be done in unusual ways.

This reasoning can be summarised in a table with characteristics in the left most column, and other columns for inferences. Putting the conclusions about actions in the final column is logical as often the other inferences are intermediate steps towards a conclusion about action.

The more skill and knowledge you have the more easily you can make good deductions about your risk management actions. It's up to you what models you believe in and what deductions you make. Fortunately, most deductions are fairly simple and don't change much between projects. To show how this works here are some things you might say in a meeting. If you refer back to the generic scheme of actions and the list of factors given above you can see how these inferences link them up. I've only given one deduction in each case but the factors will usually result in several.

| Observation | Inference | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Our deadline is absolutely fixed... | ...therefore... | ...we'd better do an analysis of risks that might occur on our critical chain and other tasks that may become critical.’ |

| ‘This project involves some critical innovation in the design of the interface. It's not been done this way before and we don't have a detailed solution worked out let alone tested and proven. Everything depends on this problem being cracked ... | ...so... | ...we had better start on it as early as possible. If this problem can't be solved we should cut our losses as soon as we know.’ |

| ‘Last time we did a project it turned sour suddenly, even though right up to the end people were still saying it was achievable. It looks like people were not reporting progress or their perception of risk accurately ... | ...consequently... | ...we need to make it a high priority to develop the honest and open culture we need for success. We must make it understood that uncertainty suppression is a bad thing and we'd like to know about uncertainties right from the start, and all the time.’ |

| ‘It's obvious how we can cut this project into evolutionary deliveries and we've already seen that we face some uncertainties around delivery... | ...so... | ...we'll devise an evolutionary delivery plan.’ |

| ‘The value of the whole project depends on there being sufficient demand for the facility once we've built it... | ...ergo... | ...is there any research we can do to improve our knowledge of that? We need to show the uncertainty in the financial model for the business case, so Monte Carlo simulation is needed to at least some degree of detail. We should look at ways to implement the facility in stages, with decision points along the way rather than committing in one decision up front.’ |

| ‘This is a classic 'change' project. We have to win support from three departments and many people will find their jobs and status have changed as a result... | ...so... | ...one thing we'll need to do is continuously monitor the views and actions of the parties involved and pre-emptively work on communicating with them about changes and how they can benefit from them.’ |

| ‘Our software suppliers are competitors to our consultants... | ...therefore... | ...that increases the risks around them doing things that are unhelpful, and acting dishonestly, maybe doing things to make the other side look bad. They'll be blaming each other most of the time and might even let things go badly if they think it will hit the other side more. In response we should perhaps consider insisting that they each take us through their own risk assessments and responses in more detail and more often than otherwise might be the case.’ |

These deductions are not a commitment to action. Not yet. You need to decide what actions are worthwhile and what do not have sufficient priority. This requires looking at the priority of actions, not ‘risks’, so try to summarise the evidence in support of decisions about actions.

When you have been through all the major factors go back through them looking for combinations that bear on the same actions. Typically there will be a number of actions that are strongly indicated by several factors and no question that they should be done. This simplifies prioritisation.

Sometimes it will not be clear whether a conclusion about an action is justified. Consider all the factors for and against.

In the case of actions based on uncertainties it may be helpful to do some thinking about the implications of each uncertainty and try to value its impact, perhaps even as a probability distribution for impact. The objective is to prioritise the action, not individual risks it addresses. It is quite possible that some risks do not justify the proposed action when considered alone but do in combination. This is hard work, so don't do it unless you really have to.

Your next summary should be a rewrite of the generic scheme, but now with more specifics, names of those assigned tasks and roles, indications of emphasis, selections from alternatives, notes on style, and so on. This can be cross referenced to the factors driving the decisions.

Your final summary will probably be a chart of actions divided into work packages that can be assigned to individuals or teams, given resource estimates, and put into the project plan.

Areas of uncertainty

In the preceding section I explained that risk is not the only consideration when designing a scheme of risk and uncertainty management actions. Other constraints are important too.

Another difference from common practice is that I use the term ‘area of uncertainty’ instead of ‘risk’. This subtle difference has important advantages:

It's easy and natural. That's probably why, when you ask people to think of risks, they give you sets of risks instead.

It eliminates the logical errors so common in risk registers where a set of risks is treated as if it were a single potential outcome.

It defers detailed analysis. This gives you a choice about where to spend time digging into more detail. Many inferences about actions do not need more detail. One technique for slightly extending the detail without going fully into the potential outcomes is to ask for leading examples of things which are uncertain within an area. This usually elicits the main thing people are worried about or hoping for.

It incorporates upside and downside outcomes/events. When you say ‘risks’ people forget about things that might turn out unexpectedly well.

Rigour by iterations

Iterations work in two ways. Firstly, you can repeat an analysis, at the same level of detail, and see what new progress you can make having had more time to think and having learned from experience, research, etc. Secondly, you can perform an analysis at a greater level of detail in an area that needs it.

Planning a project is complicated enough without trying to think through every combination of unexpected outcomes, so risk management cannot look at everything in detail. You must be selective. Several of the risk responses resulting from an initial attempt to plan risk management activities will typically be to do more analysis in specific areas or specific ways.

How does this compare with standard theory and practice?

In theory there are big differences between the approach described above and ‘standard’ theory. By ‘standard’ theory I mean the approach where you are supposed to identify risks, assess them, decide which are worthy of action, and then assign actions and owners to each individual risk that exceeds your tolerance.

However, in practice the difference is much less and what I have described is much closer to what people actually do than the standard theory. If you look at the risk register produced by a productive team under the banner of standard theory you will see that in the ‘risks’ column they have written all manner of items, almost none of which are risks, and under the ‘actions’ heading they have written a variety of actions including additional analyses they plan to perform. Quite often the actions are already planned at the time the risk register is created for the simple reason that they are part of the team's customary approach to projects i.e. they do not start with a blank list of risk responses.

Summary

Before you start listing risks and mitigation in workshops, think about the bigger picture: the full scheme of risk and uncertainty managing actions you can take. Listing specific worries is just one technique in this broader approach, and not the most powerful in many cases.

Further reading

‘Designing internal control systems’ describes a design method for creating schemes of internal controls for business and financial processes.

Evolutionary Project Management, as described by Tom Gilb (one of the key figures in this area) is characterised by several principles.

A case study on Evolutionary Project Management has been written by Stuart Woodhead, an IT project manager who had the experience of managing two nearly identical projects, one of which was a failure using conventional methods, the other being managed with evolutionary methods with great success. The case study is a very realistic description of these methods as used on a small scale (but sadly no longer available online).

Also from Tom Gilb comes this useful advice on detecting and preventing defects in a project: ‘Optimizing Software Inspections.’

A detailed discussion of risk management using the Critical Chain method (an application of Eli Goldratt's Theory of Constraints to project management) is given by Frank Patrick in ‘Critical Chain and Risk Management.’

Words © 2003 Matthew Leitch. First published 15 October 2003.