Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

Value Driven versus Target Driven planning

Contents |

The Gilb symposium on Value Driven Planning 2006

Every year Tom Gilb (www.gilb.com) hosts a week long symposium for people interested in projects, IT, and related topics. The event is by invitation only and all participants must make a presentation. It's great and attracts some interesting people from all around the world.

In 2006 the topic was ‘Value Driven Planning’ and by the last day a couple of things had clarified in my mind so I gave a short presentation on them. This is possible when the programme is evolving and deftly managed by Niels Malotaux (www.malotaux.nl/nrm/English/). There were calls for me to write my presentation up as a paper, so here it is, slightly extended, and improved by incorporating a wonderful idea from Chris Dale, (www.btt-research.com) who spoke just after me.

Two concepts we all recognise

You already know the ideas behind Value Driven and Target Driven planning, but let's just clarify the jargon.

Value Driven planning is where you plan to do the most valuable things with your resources, and of those valuable things you try to do the most valuable things first if possible. This is common sense, an everyday occurrence, and also the usual approach in management science. Whether we value alternative actions using money or utility or something else, the most common decision making methods involving putting a value on each alternative (perhaps very roughly and even unconsciously) and choosing the best, or finding the optimum level of something.

If you go shopping for a T-shirt you might look in a few shops and pick out possible T-shirts before running out of time and patience, or deciding that nothing better is likely to be found if you keep looking. At that point you choose the best T-shirt for the money from what you have seen and buy it. This is a Value Driven choice.

If you've ever studied quantitive techniques for management such as decision trees, linear programming, and almost anything about financial decision-making then you have knowledge of highly developed and long established ways of working out what the best choice is. All this thinking is Value Driven.

Target Driven planning is where you have a target or set of targets you try to reach, and you try to do what gets you to your targets. Target Driven thinking is also very familiar. It reflects the way we tend to ask people for what we want. For example, ‘May I have 2 kilos of potatoes please’, ‘Get me twelve bricks.’, and ‘I need two tonnes of sand.’ What we rarely do is say ‘This is how my values work, so please do something that will make me happy.’

Target Driven planning is common in organisations. ‘May I have 2 kilos of potatoes please’ becomes ‘Give me £2m of profit this month!’ The way we express ourselves becomes the way decisions are made and priorities set. For example, a document describing a desired computer system will usually contain some pages of non-functional requirements expressed as required performance levels e.g. recovery from backup in less than 2 hours, average response time to queries of less than 10 seconds, and so on. Many organisations have budgets, which are collections of targets for income, expenditure, and profit/surplus. Many organisations have medium term targets, such as a particular level of market share, or earnings, or turnover. Some have ‘balanced scorecards’ and then set up target levels of achievement for each year on their scorecard measures.

Target Driven thinking also draws some support from cybernetics, a scientific approach to systems and control that emphasises feedback loops.

How they differ

In Target Driven thinking the idea is that achieving the target is valuable but failing is not. The Target level marks the difference between valuable and not valuable. In Value Driven thinking, having established measures for performance, we then go on to think about where performance currently is and how we would value various alternative levels of performance. Typically, the relationship between performance level and value is fairly smooth, but there are exceptions. For example, there may be a level below which performance is just impossible to live with, or a level beyond which further increases provide no further value. There may be important benchmarks, such as levels of performance achieved by competitors, which have sharp changes in value near them.

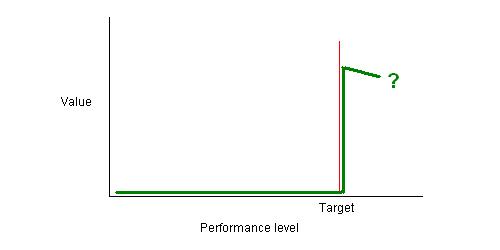

The effect of this difference on priority setting is dramatic. The Target Driven approach encourages people to think of the relationship between value and performance as a stepped function, something like this:

As performance level increases from zero the value stays at zero until the target level is reached. Once that is exceeded we hit a utility jackpot and suddenly all the value is enjoyed. After that it is not clear what happens. Going further sometimes seems like a good thing but if we go too far it is likely to prompt awkward questions.

The effect on priorities can be extraordinary. If we are very close to reaching the target and there is an action that will tip us over the threshold and hit the utility jackpot then that action becomes very high priority. On the other hand, if we are far from the target, or far beyond it then many actions that would lead to improved performance have no priority at all.

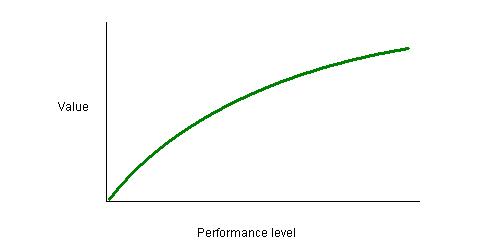

There are some real life situations where the relationship between performance and value really does have this stepped shape. For example, you can't get into the Guiness Book of World Records without exceeding the previous record. However, it is much more common in life to find that the link between performance level and value is (a) smooth, and (b) steeper for low levels of performance but flatter at high levels of performance. As Arnold Schwarzenegger said on British television many years ago ‘Money doesn't make you happy. I'm no happier now with $51m than I was when I had $50m.’ The more common curve looks something like this:

Notice that the value per increment of extra performance is greater at lower levels of performance. (That first $1m probably made Arnold a significantly happier man.) Then at higher levels it flattens out.

Value Driven planning encourages us to think of value in this way, rather than in sudden steps. Usually that means making more rational decisions about priorities. It encourages us to prioritise actions that will produce improvements on performance characteristics where we are currently at painfully low levels of performance. It does not encourage us to prioritise actions that will only move us from quite high performance to fractionally higher performance, but happen to get us over a target.

Target Driven thinking often seems able to create higher motivation than Value Driven thinking. That is partially true. Targets can create intense motivation – motivation so strong it can lead people to cheat by manipulating numbers or worse – but only if performance is just below the magic target level. Everywhere else motivation is weak. With Value Driven thinking and smoother, more realistic relationships between performance and value, motivation exists at all levels of performance but reduces appropriately as performance rises.

In a Target Driven organisation there may be serious problems in some areas but late at night the only person still working is an accountant, desperately working through the fixed asset register trying to squeeze the numbers to hit a Return on Assets bonus threshold that is tantalizingly close. Local authorities will run down their action plans looking for the ones that will get them up a level against a government target. None of this is rational.

In short, the natural way of asking someone else for something has turned into a Target Driven management system that sometimes drives some bizarre and undesirable behaviours. In contrast, Value Driven planning is closer to rational behaviour in the face of limited resources.

What is unclear at this point is whether Target Driven planning has some other advantages that offset this.

What is necessary?

Thinking back to those decision-making techniques from management science it is obvious that we don't need targets in order to decide what is more valuable to us. We don't need targets to decide what to do first. We don't even need targets to decide what is worth doing.

However, we do need to know (roughly at least) what characteristics of performance we value at all, and how much we value different levels of performance on each.

Do we, perhaps, need targets to express our desires to others? I will return to this question later.

The importance of the language we use

In my studies of risk management I have found that the words we use with people trigger them to use certain ideas and behave in certain ways. Specifically, if you ask people to list ‘risks’ they will usually list things that could go wrong. If you ask them to list ‘areas of uncertainty’ they will list things they don't know, including outcomes, and when asked for ways to manage the areas they will come up with more actions that involve learning. In short, asking for ‘areas of uncertainty’ gets people thinking more effectively about risk and uncertainty.

If we want to do Value Driven planning then I suggest we steer clear of words that will trigger Target Driven thinking. Here are some:

Target, goal, objective, trigger level, threshold: These words obviously relate strongly to Target Driven planning.

Requirement: When it comes to IT projects a word that concerns me is ‘requirement.’ When we talk of requirements we are talking of Targets. If I get my ‘requirement’ I'll be happy, but if I don't I will be unhappy. There are no degrees of requirement. The language of requirements triggers Target Driven thinking.

Words that are more likely to trigger Value Driven thinking include these:

Improve, progress, increase, reduce, grow: Chris Dale's superb question was ‘How would you like to improve?’

Value, prefer, appreciate, important: These can be used in questions like ‘Would you value an improvement of 10% in this as much as an improvement of 5% in that?’ and ‘How much would you value a turnaround of just 30 minutes?’

Giving instructions in an organisation

How can we use language to give instructions to subordinates at work without resorting to Targets? Here are some possibilities:

Express values: The approach that gives most freedom for people to think is simply to express your values and leave people to do whatever they can think of that will achieve good results measured against those values. You would need to state what dimensions of performance were valued and how much different levels of performance were valued on each dimension. This has been shown to work well in IT projects where Gilb's planning methods have been used. Words are usually insufficient to express values adequately; numbers are needed.

State constraints: If the hands-off approach feels too risky then a way to reduce the risk of inappropriate behaviour is to state some constraints along with the values.

Specify a procedure for planning: Another way to impose some limits is to insist that a particular decision-making process be followed.

Specify actions to take or policies to apply: At the other extreme you can leave people with little thinking or freedom by specifying their procedures and insisting they just follow them. This is not necessarily a demeaning procedure. We all behave according to simple rules most of the time, only occasionally thinking about changing them. For example, even though I am a self employed person with near total freedom of choice I do not meticulously prioritise every action on value. Instead, I put paying work first, raising bills second, always do my tax forms on time, and follow up anyone who seems genuinely interested in buying my services. Any time left over goes on research or writing likely to be interesting to potential clients. Usually this is enough.

Final word

Value Driven planning offers some advantages over Target Driven planning, and both are natural and familiar. The trouble with Target Driven planning is that it often distorts our thinking about what is valuable. Asking people for what we want works fine in a shop, but generates some serious problems when used in the same way in an organisation, particularly where we would prefer people to think and use their expertise to add value rather than just do what we tell them to do.

In future I'll be sticking to language that encourages Value Driven planning, and steering clear of language that might trigger Target Driven thinking.

Appendix on reporting progress

Russell Vane, who also attended the Gilb Symposium, read the above article and pointed out that Value Driven and Target Driven management approaches also differ in reporting progress. In Value Driven planning, mentions of project status usually indicate the range of performance currently expected when benefits are delivered. In Target Driven planning project status is more often a statement about the probability of achieving the target level.

Another point Russell made was that the boundaries of status categories like Red, Yellow, Green can become mini targets in themselves, with people scrambling to nudge their progress over the thresholds between these categories.

Made in England