Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

Results of an experiment in risk and uncertainty communication

by Matthew Leitch, first published 22 December 2006.

Contents |

Thank you

First, thank you to the unprecedented 214 people who participated in this experiment to look at the way words affect our thinking about risk and uncertainty. This is by far the most people to have participated in one of my online surveys and enabled reasonable coverage of the 6 experimental conditions.

Summary

If you tell someone your best guess about some quantity and add ‘But I'm no expert’, or give a range of error, or some other caveat, do they take any notice of these expressions of uncertainty? That was the practical question this study sought to answer.

The results suggest that, in the scenario studied, with the actions involved, and using the expressions of uncertainty tested, what you say makes only a small difference to preferences for actions. Consistent differences only emerged at the most summarised level of data analysis despite using 214 subjects.

In four of the six experimental conditions the estimated quantity was expressed with upper and lower bounds while in the other two no bounds were given but the estimator expressed high or low confidence in his estimate. The results suggest that stating wider bounds does increase preference for actions that reflect a higher perception of uncertainty, but bounds have to be quite wide to have an effect equivalent to statements without bounds. In this experiment the bounds were not wide enough to do this and so the effect of stating bounds was to reduce perceived uncertainty.

Perhaps stating upper and lower bounds gives an estimate extra credibility.

Experimental design

The experiment was performed online using the Internal Controls Design website and participants were volunteers who were responding to e-mails posted on various professional discussion lists.

When participants arrived at the experiment page the instructions told them to read the text of a hypothetical scenario about trying to sell an antique clock, then rate five given actions on a scale from Awful to Great, and give a confidence level in respect of each rating.

The text of the scenario was slightly altered in each of the 6 experimental conditions and was this:

‘Scenario: An elderly relative you were fond of has died and left you a clock. It is big and ugly but very old and in excellent working condition. You have nowhere to put it so decide to try to sell it and show it to an old family friend who repairs clocks as a hobby. The friend recognises the maker and says it is rare to see one in such good condition. He says “[SPECIAL TEXT]” He then tells you he knows a dealer who might make an offer. That evening the dealer calls and offers £600 for the clock. You say you need to think and will call back the next day with your answer.’

The experimental conditions and the special text for each were as follows:

Expert Point: ‘I'm an expert at valuing fine antique clocks and after careful consideration of your clock, its maker, condition, and current interest in this type of piece I can tell you that you would get about £600 for that at auction.’

Guessed Point: ‘I'm no valuation expert, but I should think you would get about £600 for that at auction.’

Point + Tiny Range: ‘I'm no valuation expert, but I should think you would get about £600, but could be as low as £500 or as high as £700, for that at auction.’

Point + Narrow Range: ‘I'm no valuation expert, but I should think you would get about £600, but could be as low as £400 or as high as £800, for that at auction.’

Tiny Range: ‘I'm no valuation expert, but I should think you would get between £500 and £700 for that at auction.’

Narrow Range: ‘I'm no valuation expert, but I should think you would get between £400 and £800 for that at auction.’

The actions to be rated were as follows:

‘Get another valuation.’

‘Accept the dealer's offer.’

‘Offer to sell to the dealer for £650.’

‘Offer to sell to the dealer for £900.’

‘Just take the clock to sell at auction.’

[The second range, £400 to £800, is described as ‘Narrow’ because it is still some way short of the £900 counter offer. A ‘Wide’ range would be something like £200 to £1,000.]

Respondents were also given the opportunity to comment, which many did, giving further insight into the thinking behind some patterns of answers.

Good answers to the scenario

As with most of the scenarios used in my research there are no right answers. However, we can identify ratings that were popular among respondents and also consider the extent to which each action is open, honest, and rational. In other scenarios I have studied the most supported actions are usually the open, honest, rational ones but with much support for other actions too. This clock scenario was just the same.

Since there were only small differences in the responses in each experimental condition we can usefully consider all 214 responses as one population. This analysis shows that:

By far the most popular single action was to get another valuation.

Almost everyone shunned accepting the dealer's offer or counter offering just £650.

Respondents were roughly equally for or against counter offering £900 or going to auction.

The most popular pattern of answers was to rate getting another valuation as ‘Good’ or ‘Great’ but rate all others as neutral or below. The next most popular patterns were to support another valuation and then also the counter offer of £900, going to auction, or both.

My assessment of the actions is that, given at least some desire to get good money for the clock, the preference for actions should reflect the perceived uncertainty about the value that it could fetch if more effort were made. Specifically, if your uncertainty is high then you should be inclined towards getting another valuation, counter offering £900, or going to an auction where you can set a reserve price and, in effect, see what valuation several dealers put on it.

In contrast, if your uncertainty is low it will seem to make more sense to waste no more time on it and just accept the offer, or counter offer at just £50 more. Twelve participants made this choice, of whom just 3 were in what were intended to be the lower certainty conditions.

Furthermore, in this situation even the most earnest and expert statements about what will be achieved at auction should be considered little more than educated guess work. Therefore, the good actions seem to be to get another valuation, counter offer at £900, and to go to auction.

[Usability testing of the scenario before the study was launched led to a change in the scenario wording. Originally it said that the clock was left by a relative you had never met. This triggered one tester to say the clock was ‘found money’ and he had no desire to work to get more for it. This is a behaviour that has been reported before in studies of valuation and so the wording was changed to something that usually produces more desire to get a good price regardless of how wealthy the seller is. The wording actually used in the study was that the relative was someone you were fond of. Some respondents commented that in reality they could not bring themselves to sell such a clock.]

Effect of different statements about the estimate

When the effect of different experimental conditions was analysed for each action's ratings individually there were no solid findings. As more responses were added to the database the apparent effect of different conditions continued to shift. Furthermore, there was a lack of logical consistency between conditions. For example, if ‘Point + Tiny Range’ gives ratings of an action above ‘Point + Narrow Range’ then ‘Tiny Range’ should also give ratings for that action above ‘Narrow Range". Although there was a tendency for things to work consistently and in the sensible direction it was weak.

However, taken together across all actions the impact of the conditions could just be discerned and seems stable, judging from the stability of the differences as results came in and the consistency of the direction of effects.

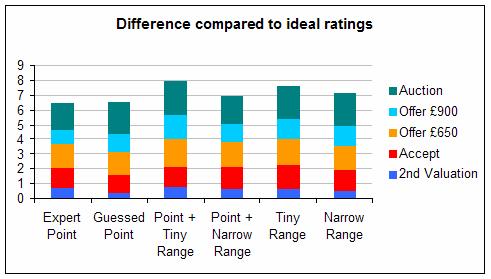

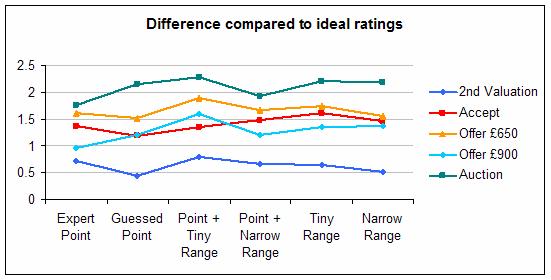

The following graphs show the average absolute numerical difference between ratings given, translated into numbers (Awful = 0, Poor = 1, Neutral = 2, Good = 3, Great = 4) and an ‘ideal’ profile (4,0,0,3,4) believed to reflect a sensible response to high perceived uncertainty.

The less the difference the higher the perceived uncertainty.

This first graph shows the effect as a stacked bar chart so that the overall pattern can be seen.

As you can see, although ‘Guessed Point’ seems to convey no more uncertainty than an ‘Expert Point’, at least widening the range increases the uncertainty conveyed, as you would expect.

Furthermore, a single point estimate given by someone who claims lots of expertise and careful consideration is less narrowing than a narrow numerical range, even when prefaced with the words ‘I'm no expert.’ Perhaps giving a numerical range confers credibility on ill-educated guesses of very-hard-to-estimate numbers.

This is an important practical finding that is well worth trying to replicate.

[This pattern remains even when the ‘ideal’ profile is varied slightly.]

This second graph shows the effect as a line chart so that the pattern for each individual action can be judged more accurately.

Comments by respondents

Excluding comments purely about the survey or experiences with clocks, the respondent comments were:

‘(1) I'm optimizing for time. (2) Getting maximum value doesn't matter a lot to me, but I know it makes sense to get another valuation; it could be worth thousands. (3) I'm either going to get another valuation or take the dealer's offer; I'm not interested in risking giving offense for a small increment.’

‘All of the above are, it seems to me, equally good ideas. None of them would be great for me. I'd try to swap it to a museum in return for lifetime visiting rights to the museum’

‘Because the family friend is not an expert, it is wise to get an independent appraisal. Several questions – how trustworthy is the family friend? Would the family friend and the dealer make a pact to buy the clock at a very low price, sell it for a huge profit, and split the money?’

‘Depending what other valuations you receive will dictate whether you offer to sell at the 2 prices and/or auction.’

‘Do not make decision when you have no good knowledge or information about the subject matter. Gathering more information is a good move which will lead to more confident decision making. Sell at the auction is the last resort if you fail to gather information about the market price of the clock. However, it requires right bidders (i.e. collectors of old clock) to be there during the auction. Otherwise, the bidding price may not reach the price offered by the dealer or in the worst case scenario, nobody will bid for the clock. ’

‘Do some personal research on the value (Great – 100%)’

‘How can you put a figure on the value of the certainty of friendship?’

‘My take is that this is found money, I am very busy and don't have time to fool with something like haggling over an inherited clock and it's more money than I had 5 minutes ago BUT I don't especially have a need for the additional money that I might get from negotiation or additional research.’

‘I like to work with as much info as possible – another valuation would be good. Accepting the dealer's offer is probably not too good a choice – he likely is offering less than value. An offer to sell at a slightly elevated or elevated value tells something about the dealer's original offer. (If he negotiates upward, then the original offer was likely a low-ball offer.) The higher the offering back to the dealer, the more likely you'll get a feel for how reasonable his first offer was. A sale at auction without knowing what the value is would put me at a disadvantage for setting minimum bids and such.’

‘I think the dealer knows the value of the clock on the open market and is offering below, so he can make a profit. No problem – that's business. If I really want to know the value on the open market, I would have it appraised or take it to the open market (auction).’

‘I would accept the offer because pursuing any alternative would take too much time (opportunity cost).’

‘I would not sell the clock for less than 700’

‘I would think of the clock as a windfall and very lucky. I would also roll the dice and let chance/auction determine the value (with a reserve price of $600 of course – hedging my bet)!’

‘I'm not clear on the last option. If the seller can place a limit on the item in the auction so that it would not sell below a certain value, then he could specify a high value and be sure of not getting less than the original offer or some higher value. In that case, I would rate the option higher with more confidence. But, it is really a case of trading time and effort for potentially increasing profit from a windfall. That is a subjective decision that needs to be based on the individual's relative needs for time and money.’

‘My answers reflect my uncertain knowledge of the dealer e.g., is he reputable and honest, would he be likely to get angry if I don't accept his offer right away, would his offer still stand a week from now after I get additional information, etc. Unless I'm in a big rush, or just don't want to deal with the clock (which might be the case if the $$ involved make it not worth my time), there's no advantage to settling before knowing what it's really worth. I'm also influenced by the fact that I used to buy weird what-nots at yard sales and resell them on ebay for a tidy profit, so I kind of enjoy this sort of thing.’

‘One must assume the 'awful' versus 'great' ratings apply to the issue of maximizing profit. eBay (auction) has changed thinking about this scenario to a very large degee. As recently as 5 years ago, I would have taken 600, especially for something that has a niche market. Now, you can sell almost anything at auction to a very large market via eBay.’

‘Relationships are at stake. The best thing to do is to get another opinion. If it is the same or close, accept the first dealer's offer. Avoid transaction costs. But if it is very different, go to auction or accept the higher bid.’

‘Selected action takes into consideration the time value of money, coupled with trust in the assessment of the subject-matter expert (the family friend who's the expert on clocks). It wouldn't be worth five minutes more of my time to deal with this problem. If I find later there was collusion between the dealer and family friend, the family friend wouldn't be welcome in the house any longer. . . .’

‘Set 600 as the reserve at auction.’

‘Sight unseen the dealer makes an offer. Not a chance I'm just going to give it to him at suggested price, or risk getting less than it is really worth by making up a counter offer or taking it to auction.’

‘Suggesting £900 would enable you to assess the real value of the clock.’

‘The awful decisions are only based on choosing those actions before getting a second or third valuation. Those actions may become acceptable after you have received additional valuations.’

‘The friend's opinion may not be dependable. The only hard information is that the dealer is prepared to pay 600. Since this is more likely to be a low offer than a high one, I might subjectively estimate the 50-percentile market price to be 900 with a 95%-ile upper bound of perhaps 1800. On that basis, offering 900 (option 4) might be considered a neutral decision with maybe 50% certainty. An offer of 650 (option 3) might be considered poor with maybe 70% confidence. An offer of 600 (option 2) might be considered poor with 95% confidence. Getting another valuation (option 1) may involve some cost but would provide additional information, which would eliminate some of the risk of selling the clock for way too little. I'll rate it as good with 95% confidence. Going straight to auction (option 5) would expose us in an unbiased way to the market so the most likely outcome would be expected to be neutral. However, since the results could range from awful to excellent depending on how many bidders are interested and other factors, I'll only give 30% certainty.’

‘Time is money, sure. But you will regret “selling cheap” all your life and this compensates the additional time looking for a “right offer”.’

Respondent profile

Respondents were invited to participate using the following professional discussion lists on the Internet:

RISKANAL: for risk analysts.

Audit-l: for auditors

PMA Forum: for performance management.

Uncertainty: for anyone interested in that subject.

Respondents gathered this way are usually mostly from the USA and UK.

214 people volunteered. They were allocated to experimental conditions randomly giving the following number of subjects in each condition:

| Condition | No. of subjects |

|---|---|

| Expert Point | 33 |

| Guessed Point | 39 |

| Point + Tiny Range | 25 |

| Point + Narrow Range | 40 |

| Tiny Range | 34 |

| Narrow Range | 43 |

Words © 2006 Matthew Leitch. First published 22 December 2006.