Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

Individual differences in risk and uncertainty management: results of a survey on risk and uncertainty management

by Matthew Leitch; first published 8 May 2006.

Contents |

Thank you

First, thank you to everyone who responded to this survey. The response was at least twice that to any previous survey in this series, with nearly everyone interested to know how their results compared with others. Several respondents wrote saying how interesting they had found the experience and the evidence is that, despite the time needed to do the survey, many more people than usual persisted until the end.

Summary

The survey probed differences between people in how they think about risk and uncertainty in business situations.

The survey presented respondents with four different hypothetical scenarios designed to probe beliefs about how to manage risk and uncertainty. In each scenario they were offered five potential actions and asked to rate each action individually as either Awful, Poor, Neutral, Good, or Great. They also had to give a certainty rating between 0% and 100% for each rating of an action.

On some actions respondents agreed quite closely on the rating. For example, almost everyone thought it a good idea to see the evidence for a disputed technical problem oneself. On other actions there was a great deal of disagreement. For example, respondents were almost equally divided on whether it was a good idea to start a creative project by stating specific financial targets.

Statistical analysis of the action ratings showed that certain ratings correlated. For example, people who thought setting targets for the creative project was a good idea also tended to think that saying nothing about a serious potential technical problem on a building project was a good idea, or at least not as bad as others thought. The target setters were also more likely to favour pushing harder on products that were selling less well than expected and were correspondingly less inclined to shift focus towards products that were doing well, or at least better than expected.

Looking at the full correlation matrix it was possible to perform a manual factor analysis and this revealed the likely effect of a number of beliefs. The main factor was a tendency to prefer target setting, hold to original targets, and not disclose information about risks and uncertainties. Other tendencies were a tendency to persuade by giving extreme descriptions, a tendency to be influenced by emerging data (the opposite of the target setting style), and a desire to investigate and explain.

There were no right answers to this survey. However, some actions were more preferred than others and some seem to me more rational, honest, and objective than others. In previous publications I have argued that a number of cognitive and social factors tend to push us towards a blinkered view of the future, suppression of our uncertainties, and a resulting failure to manage risk and uncertainty effectively. Major objectives of risk management programmes should be to help people think more widely about the future and deal effectively with this more realistic outlook.

For the purposes of analysing the survey data a model profile of answers was selected based on compliance with the a small set of principles. These principles are that (1) objectivity and rationality are desirable, (2) we are frequently uncertain and facing risks and need to acknowledge this and act in accordance with it, (3) focus on single future outcomes is usually at the expense of an objective view of the future, which requires a recognition of uncertainty, (4) it is better to be honest, and (5) these considerations are very important and usually outweigh others. These principles imply a rating for each action.

Collectively, respondents behaved in accordance with the principles stated above in that the most highly rated actions were always the ones most consistent with the principles.

However, very few respondents consistently rated actions in accordance with the most preferred ratings or in accordance with the risk and uncertainty principles. This individual inconsistency may be because the underlying issues had not been thought about previously by many respondents, or perhaps because other considerations over-rode uncertainty in some scenarios.

However, I suspect the main reason for departing from the theoretical ideal of the principles was usually a failure to see the dangers in certain actions. Many people thought it was fine to say nothing about a worrying risk that had developed until they had found a solution, at which point they could explain it all. In the real case of the Holyrood building project, on which this scenario was loosely based, civil servants took exactly this approach. Unfortunately, they could not think of a solution and consequently kept quiet far too long. They did not see the dangers in their approach and neither did many respondents to the survey. Happily, the most highly rated approach to this problem was to give a full briefing of risks and uncertainties right away, but the results suggest that many people would not actually do so.

There were slight differences between different groups of respondents. The auditors tended to give answers further away from the principles than others and were particularly prone to concealing risks and exaggerating both good and bad news in pursuit of a reaction. People who were students or sole traders tended to score closest to the principles, while people in an organizational hierarchy scored further away, with ‘middle’ managers being furthest from the principles as well as spending the least amount of time on the survey, on average. However, these differences are slight and it is likely that the wide variations between individuals are driven mainly by other things.

Taken as a whole, this exploratory study suggests that, although the most popular actions are generally those that follow the principles of risk and uncertainty management listed above, there will often be a high risk of people acting otherwise, with potentially damaging consequences. Organizations should seek to understand better what their people think and promote the practices they believe are appropriate, rather than leaving things to chance. The detailed findings of the survey suggest some unexpected but powerful tactics for doing that.

What did respondents agree on?

Two measures of (dis)agreement were calculated for each of the 20 actions to be rated. One was the percentage of ratings that were the most popular rating for that action. (This is called ‘Most popular %’ in the table below, and higher numbers mean greater agreement.) The other was the percentage of ratings that were in the minority, where this was calculated as the sum of Good and Great ratings, or the sum of Poor and Awful ratings, whichever was lower. (This is called ‘Minority %’ in the table below, and lower numbers mean greater agreement.)

| No. | Action summary | Most popular % | Minority % | Ave. certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Set targets beforehand | 31 | 42 | 78 |

| 2 | Sell the heights of success | 46 | 18 | 76 |

| 3 | Give best estimate | 34 | 40 | 75 |

| 4 | Describe full range | 47 | 11 | 78 |

| 5 | Avoid discussing outcomes | 55 | 13 | 84 |

| 6 | Investigate under performance | 55 | 6 | 81 |

| 7 | Push under performers | 42 | 20 | 74 |

| 8 | Investigate over performance | 54 | 1 | 84 |

| 9 | Shift to surprisingly successful lines | 37 | 24 | 71 |

| 10 | Shift to highest contributors | 49 | 11 | 75 |

| 11 | Say nothing | 36 | 11 | 81 |

| 12 | Visit roof company | 45 | 4 | 81 |

| 13 | Tell the worst | 36 | 24 | 77 |

| 14 | Find a solution, then disclose | 49 | 22 | 81 |

| 15 | Full briefing | 54 | 4 | 88 |

| 16 | Out-boast opponents | 31 | 33 | 77 |

| 17 | Explain common uncertainties | 54 | 6 | 82 |

| 18 | Explain your flexibility | 60 | 2 | 83 |

| 19 | Short and positive presentation | 49 | 15 | 77 |

| 20 | Show knowledge of past surprises | 55 | 9 | 78 |

We can think of the minority percentage as an indication of how hard it would be to get a group of managers to agree to do the right thing. Clearly some actions caused more disagreement than others. Seven of the 20 items left less than 10% of people in the minority – so would be agreed relatively easily – while three items had a minority of more than 30% and could easily go the wrong way (especially if many respondents were Neutral on the item).

The minority percentage is also an indication of how many managers typically hold views on these points that are out of line with the majority and might be, perhaps routinely, making decisions that others would regard as poor.

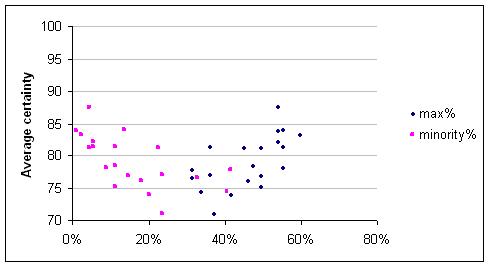

You can also see that the ratings that people disagreed on most tended to be the ones they felt the least certain when giving the ratings. Here is a scatter plot showing both measures of agreement against average certainty for each of the 20 actions.

Which preferences were linked and why?

The ratings were turned into numbers (Awful = 0, Poor = 1, Neutral = 2, Good = 3, and Great = 4) and the answers by all 89 respondents were correlated taking every pair of actions in turn. This created a correlation matrix and revealed some interesting links between ratings, often across different scenarios. Here are the highest 7 correlations, with suggestions as to what belief might lie behind them.

| Action | Correlation | Action | Possible belief |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shift to highest contributors | 0.58 | Shift to surprisingly good performers | Data from experience should drive actions. |

| Set targets beforehand | 0.48 | Push under-performers | Control works by negative feedback loops |

| Short and positive presentation | 0.43 | Out-boast the competition | To persuade it is good to be ‘confident’ and ‘positive’. |

| Investigate under-performance | -0.35 | Shift to surprisingly successful lines | Negative feedback control thinking versus learning from experience. |

| Find a solution, then disclose risk | 0.34 | Short and positive presentation | Giving bad news is career damaging. |

| Find a solution, then disclose risk | 0.33 | Say nothing | Giving bad news is career damaging. |

| Visit roof company | 0.33 | Shift to the highest contributor | It's good to get and respond to facts. |

The actions were rearranged in the correlation matrix to group together the ones that tended to have correlated answers, giving a manual factor analysis. (There was not enough data for a formal analysis.) Even though the groups are faint they are suggestive and help make some sense of the data.

| Action summary | No. | 20 | 5 | 15 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 14 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 18 | 4 |

| show past knowledge and surprises | 20 | 1 | -0.08 | -0.18 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.13 | 0.02 | -0.06 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.01 | -0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | -0.1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| avoid discussion of outcomes | 5 | -0.08 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.16 | -0.07 | -0.13 | 0.2 | -0.05 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.07 | -0.11 | -0.16 | 0 | 0.06 | -0.11 |

| full briefing | 15 | -0.18 | 0.21 | 1 | -0.17 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.02 | -0.23 | -0.19 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0 |

| shift to surprisingly successful lines | 9 | 0.11 | 0.16 | -0.17 | 1 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.2 | 0.16 | -0.05 | -0.03 | 0.15 | -0.35 | -0.05 | -0.09 | -0.07 | 0.06 |

| shift to highest contributors | 10 | 0.05 | -0.07 | 0 | 0.58 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0 | -0.09 | 0.19 | -0.18 | -0.04 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.13 |

| visit roof company | 12 | 0.1 | -0.13 | 0 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.1 | -0.03 | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.21 | -0.03 | -0.02 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.05 | -0.01 |

| give best estimate | 3 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.01 | -0.1 |

| sell the heights of success | 2 | 0.02 | -0.05 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.05 | -0.03 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.22 | -0.03 | -0.08 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.07 | -0.26 |

| tell the worst | 13 | -0.06 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0 | -0.11 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.16 | -0.18 | -0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | -0.06 | -0.18 | -0.32 | -0.05 | 0.01 |

| out-boast opponents | 16 | -0.05 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.1 | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.04 | -0.06 | -0.29 | 0.01 | -0.14 |

| short and positive | 19 | -0.09 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.27 | -0.06 | -0.04 | -0.19 | -0.12 | -0.2 |

| find a solution, then disclose | 14 | -0.01 | 0.12 | -0.23 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.01 | -0.03 | -0.18 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.1 | -0.01 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0 |

| say nothing | 11 | -0.05 | 0.17 | -0.19 | -0.05 | 0 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.08 | -0.04 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.21 | -0.14 | 0.02 | -0.04 | -0.02 |

| push under performers | 7 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.18 | -0.03 | -0.09 | -0.02 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.01 | -0.21 | 0.24 | 0 |

| set targets beforehand | 1 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.3 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.03 | -0.06 | 0.22 | -0.14 |

| investigate under performance | 6 | -0.1 | -0.11 | 0.14 | -0.35 | -0.18 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.07 | -0.06 | 0.04 | -0.06 | 0.1 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| investigate over performance | 8 | -0.1 | -0.16 | 0 | -0.05 | -0.04 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.06 | -0.18 | -0.06 | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.14 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.08 |

| explain common uncertainties | 17 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.11 | -0.09 | -0.01 | 0.09 | 0.05 | -0.06 | -0.32 | -0.29 | -0.19 | 0.16 | 0.02 | -0.21 | -0.06 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.08 |

| explain your flexibility | 18 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | -0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.07 | -0.05 | 0.01 | -0.12 | 0.11 | -0.04 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 1 | -0.01 |

| describe full range | 4 | 0.11 | -0.11 | 0 | 0.06 | -0.13 | -0.01 | -0.1 | -0.26 | 0.01 | -0.14 | -0.2 | 0 | -0.02 | 0 | -0.14 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.08 | -0.01 | 1 |

Were risk and uncertainty responded to rationally?

There are no right answers to this survey. However, a person acting according to the principles below would give a certain set of answers to the survey and these were used as a profile against which to compare respondents' answers.

The principles are that:

Objectivity and rationality are desirable.

We usually face risk and uncertainty and need to acknowledge this and act in accordance with it.

Focus on single future outcomes is usually at the expense of an objective view of the future, which requires a recognition of uncertainty.

It is better to be honest.

These considerations are very important and usually outweigh others.

These principles imply a rating for each action, which will be called the Principles Model for the purposes of this study.

Scenario 1 – starting a creative team: By Principles 2 and 3 all the actions that involve stating a single future level of outcome are Awful. The dangers include killing ideas that would have achieved more or less than the initial expectation or target, anchoring guesstimates of the potential of ideas, and failing to stimulate precautions against failure and efforts towards greatness. In the circumstances it was clear that the future impact was highly uncertain. As one respondent put it ‘At first I thought it would be a good idea to put up some clear targets, but then I thought “How would I know what they should be?”’ Talking only of the highest level of impact that might be achieved in order to stimulate the team also fails on Principle 1 because it is not objective. Avoiding discussion of outcomes was a neutral action according to the principles and it would have been possible to tell the team that developing expectations for outcomes was part of the work to be done.

Scenario 2 – responding to sales figures: Sales that are not as expected in a business plan can be because the plan was wrong or because the execution was flawed, or both. In this scenario the sales expectations were developed before the business existed, purely to raise finance, and high reliability is not expected. By Principle 2 this uncertainty needs to be recognised and responded to, which in this case means recognising that expectations for each product need to move from the initial expectations towards the actual level of sales, although investigation may reveal important factors that upset this. Consequently, investigating the factors behind performance is at least a Good idea and focusing on the surprisingly successful product is particularly valuable because it is more likely to be in the future mix and successes are harder to find than failures. Trying harder to sell the under-performing product is an Awful action because it moves resources in the wrong direction (though with lower certainty because of the possibility that investigation reveals flawed execution). Both shifts of resources towards success are Good or Great.

Scenario 3 – disclosure of an emerging project risk: Saying nothing about the risk is clearly Awful under Principles 2 and 4. Waiting until you have a solution and then disclosing also fails for the same reasons, and in practice often amounts to the same thing as saying nothing because people cannot think of a solution quickly or at all. Disclosing immediately but pointing out the very worst that could happen as a result fails on Principle 1 because it is deliberately biased. Visiting the roof company to examine the alleged problem yourself is a Great action that will reduce some key uncertainties, particularly as none of the parties can be trusted to be open and honest in the dispute that has arisen. Making a proper presentation of all the major risks and uncertainties of the project is something that should have been done long ago and is Great.

Scenario 4 – competitive selling: Matching the claims and confident assertions of the competitor is an Awful action, failing on Principles 1, 2, 3, and 4. Not only that but since the competitor's presentation is too confident of results to be credible there is every chance that the audience has also realised this. Explaining the uncertainties that would affect projections about any similar venture is a Great way to make sure the audience understands the competitors have been dishonest, while at the same time demonstrating superior knowledge and a responsible attitude. Explaining the flexibility in your strategy is also Great under Principle 2 and will reassure the audience. Being short and wholly positive has the virtue of being short, but as it ignores uncertainty it is just another version of the first action, so also Awful. Finally, reminding the audience of past surprises is a Great way to counter any tendency towards mental blinkers and helps them adhere to Principle 2. There is no need for this material to be long or critical of others.

Collective wisdom

The main observation is that, collectively, respondents rated actions similarly to the Principles Model. If you are a respondent there were probably several things in the preceding analysis that you disagreed with, but, overall, the level of agreement is impressive. The following table sets out where the collective wisdom of respondents agreed and disagreed with the Principles Model.

| Action summary | Agreement with Principles | Disagreement with Principles | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set targets beforehand | Slightly more respondents against this than for it, and more Awful ratings than Great ratings. | ||

| Sell the heights of success | Not rated as highly as Describe full range. | Large majority in favour of this action. | |

| Give best estimate | Not rated as highly as Describe full range. | Slight majority in favour of this action. | |

| Describe full range | Heavily preferred. | ||

| Avoid discussing outcomes | Heavy majority against this. | Not relevant to Principles | |

| Investigate under performance | Heavy majority in favour, but not as much as for investigating over-performance. | ||

| Push under performers | Majority against this action. | ||

| Investigate over performance | Heavy majority in favour, and more so than for investigating under-performance. | ||

| Shift to surprisingly successful lines | Majority in favour of this. | ||

| Shift to highest contributors | Heavy majority in favour of this. | ||

| Say nothing | Very heavy majority against this, with more than a third rating it Awful. | ||

| Visit roof company | Heavy majority in favour of this action. | ||

| Tell the worst | Majority against this. | ||

| Find a solution, then disclose | Rated much lower than giving a full briefing. | Heavy majority in favour of this action. | |

| Full briefing | Enormous majority in favour of this, with 54% rating it Great. | ||

| Out-boast opponents | Slight majority against this action. | ||

| Explain common uncertainties | Heavy majority against this. | ||

| Explain your flexibility | Heavy majority in favour. | ||

| Short and positive presentation | Majority against. | ||

| Show knowledge of past surprises | Heavy majority in favour. |

In the above analysis I have largely ignored disagreement between respondents and the Principles Model as to the exact rating i.e. Good vs Great, and Poor vs Awful. The extreme ratings ‘Awful’ and ‘Great’ were relatively rare among respondents, compared with the Principles.

On three items the majority view disagreed with the Principles Model:

Sell the heights of success: The action was to talk up the heights of success that might be achieved and avoid discussion of possible failure or disappointment. Compared with the other two actions involving statements of a single future outcome this has the advantage of expanding expectations of the team in the upper region. It also has the attraction of generating excitement and the possibility of increasing motivation among team members. The dangers that perhaps many respondents underestimated are those coming from the two ways in which the statements are not objective. Firstly they are biased towards upper achievements and so vulnerable to disappointing news in future. Happy expectations need a rational foundation and if the next few weeks of work bring evidence that is not consistent with the rosy future set out at the start the disillusionment will be greater. Secondly, because lower levels of achievement have not been discussed and, indeed, the happy tone will discourage such considerations in future too, there is a great risk that even basic precautions against poor results will not be taken. If a really exciting and successful product idea does not emerge then those dull ideas that the team have been ignoring for weeks will need urgent attention. Also, when it comes to projecting the future results from products that have been thought of the tendency will be to make estimates that are in line with the initial high expectations. Humans are extremely vulnerable to this and will anchor even to numbers they know to have been selected at random.

Give best estimate: Although this action was only slightly preferred (and in fact more people thought it Awful than Great) the preference is puzzling. It may have benefitted from being immediately after the much more popular action to sell the heights of success.

Find a solution, then disclose: This item is a cause for concern. The building project scenario was very loosely based on a real case: the disasterous Holyrood building project to create a new home for the Scottish Parliament. A public enquiry was held after costs spiralled 1,000% over budget. At one point in the enquiry civil servants were asked why they had not discussed with the responsible minister the persistent failure of the architect to come up with a design that was within budget. They had decided to find a solution and then raise the issue. One said there was no point in speaking to the minister about it if all you could do was ‘share your anxieties.’ Sadly they did not find a solution and so said nothing for far too long. In this real case the people concerned did not see the dangers in their approach, and perhaps many respondents to the survey didn't see those dangers either.

As you can see from the Respondent Profile later in this report, the respondents were volunteers who heard about the survey through one of a number of Internet discussion lists for performance managers, auditors, risk managers, and risk analysts. Could their high degree of agreement with the Principles Model be because of their special knowledge and roles? Perhaps, but if this were so the Performance Managers (for whom risk and uncertainty is not such a focus as for auditors and risk specialists) should have scored further away from the Principles Model. In fact they were closer to the model than the Auditors.

Individual variations

Having said that the collective wisdom was close to the Principles Model there were considerable variations between individuals and no respondent made all their choices in agreement with the For/Against recommendations of the Principles Model, let alone agreeing on all the ratings.

Firstly, here is the analysis, scenario by scenario, reducing the answers to just ‘Yes’ (if Good or Great) or ‘No’ (if Neutral, Poor, or Awful):

Scenario 1: The fifth action wasn't really relevant to the Principles so the model profile for this scenario is just ‘NNNY’, which was the choice of just 11 out of the 89 respondents (i.e. 12%), though it was still the second most common profile after ‘NYNY’ with 19 (i.e. 21%).

Scenario 2: The Principles Model profile for this scenario was ‘YNYYY’ which was the most popular profile with 22 takers (i.e. 25%).

Scenario 3: The Principles Model profile for this scenario was ‘NYNNY’ which was the second most popular profile with 11 takers (i.e. 12%). The most popular profile was ‘NYNYY’ with 34 respondents (i.e. 38%) thanks to the seductive appeal of keeping the news quiet until a solution had been found.

Scenario 4: The Principles Model profile for this scenario was ‘NYYNY’ which was the most popular profile with 31 respondents (i.e. 35%).

Looking across all scenarios, no respondent chose the Principles Model profile in more than two scenarios. The model profile was chosen in two scenarios by 18 respondents, in one scenario by 39 respondents, and 32 respondents didn't choose the model profile in any scenario.

Potential remediation strategies

Suppose the leaders of an organization decided that they wanted more of their managers to prefer actions in accordance with the Principles Model or something similar. What strategies are suggested by this research?

Tap into collective wisdom carefully: People are influenced by what others think so bringing out that collective wisdom will be helpful in moving minority views towards the more popular views, which is usually what organizations will want to do. However, this has to be done the right way, i.e. by asking who believes what and pointing out the most popular patterns of answer. If you asked a group of managers if they agree with all the suggested answers (whatever your principles) the answer will be a resounding ‘No!’ because no profile of answers is held by a majority. Analysis of the certainty ratings showed that those in the minority tended to less sure of the answers and so, presumably, more open to accepting alternatives. This is also helpful, except in the few cases where the majority favours an action that is not a good one.

Pay attention to individual differences: Between the survey respondents there were considerable variations, ranging from a risk management consultant whose ratings were extremely close to the Principles Model, to a former financial controller whose history of unpleasant experiences in a large company has taught her to avoid passing on bad news and whose answers were very far from the Principles Model. The survey does not tell us what groups typically are closer and which further away, but it is at least clear that large variations exist. It may be helpful to focus initially on some groups, perhaps those whose answers are already close to an organization's preferred model.

Make sure the best actions are considered: In the survey some actions were highly rated that were not favoured by the Principles Model. However, there was always an alternative action that was consistent with the Principles Model and even more highly rated by respondents. Therefore one strategy that may encourage people to take the correct action in practice is to ensure that the best action is considered and not overlooked. If someone, or a document, suggests giving a full risk report, for example, then there is less risk of people forgetting that option and just keeping the worry to themselves while they look for a solution.

Point out the dangers of competing actions: The frequent preference for the action favoured by the Principles Model suggests that perhaps many people do not need to be reminded that these actions are a good thing. What they do need, however, is an explanation of the hidden dangers in competing actions that are not consistent with the model. If the model action stands out more then it is more likely to be taken. Understanding the dangers also equips a manager to discourage colleagues from taking inappropriate actions.

Promote specific communication skills: Following the model in some of the scenarios is only possible if you are able to use appropriate communication strategies. For example, if you don't know how to discuss the flexibility in a plan concisely and clearly you may not have time to cover risk and uncertainty properly in a sales pitch. If you do not know how to tell your boss about an area of uncertainty to which there currently is no solution without your boss getting unpleasant then one or both of you need to learn to talk about uncertainty in a different way.

Differences between groups of respondents

In the survey, respondents were asked which best described their role and background: Performance Manager, Risk Manager, Internal or External Auditor, or Other. They were also asked a question to assess their position in an organizational hierarchy.

To study possible differences between groups of respondents their ratings were turned into a more exact measure of difference from the Principles Model. The Principles Model was turned into a profile of ratings (Awful = 0 to Great = 4 as before) and each respondent was given a score that was the sum of the absolute difference between their ratings and the Principles Model. The lower the respondent's score the closer their match with the model. This score was analysed in various ways.

Lower scores are ‘better’ with respect to the Principles Model.

Overall the differences tended to be slight and probably not very reliable. The number of respondents in each group was not equal of course and some combinations of role and pecking order had many more respondents than others.

| Pecking order | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role/background | Sole | Top | Middle | Bottom | Total |

| Performance Manager | 25.75 | 23.75 | 34.33 | 28.57 | 27.09 |

| Risk Manager | n/a | 24.5 | 28 | 25.75 | 25.91 |

| Auditor | 30 | 33.86 | 29 | 28.75 | 30.33 |

| Other | 25 | 26.43 | 27.5 | 23.6 | 26.19 |

| Total | 25.73 | 27.31 | 28.67 | 27.36 | 27.49 |

The strongest difference is the high score by auditors. Looking across the individual actions it seems that auditors score further from the model on most actions but dramatically so for the two major factors in the factor analysis linked to target setting, hiding risks, and exaggerating good and bad news. As someone who has been an external auditor for most of his career I find this hard to understand but perhaps people who have been on the receiving end of an audit report would have less difficulty.

It is also noticeable that people outside a corporate hierarchy score closer to the model, while the much maligned middle managers score furthest from the model (as well as being the group that spent least time on the survey on average).

[The time spent on the survey was measured by a timer within the web page, but obviously respondents working on the survey would be interrupted. Looking at the outliers it was decided to assume that if a respondent spent more than 400 seconds on one scenario then they had been interrupted. In these cases the recorded time was replaced by the average time across other respondents for that scenario.]

Respondent profile

The survey was open during late April and early May 2006.

Respondents were volunteers who heard about the survey through any of four Internet discussion lists:

PMA Forum: used mostly by performance managers and others interested in performance measurement and management.

RISKANAL: used by people involved in risk analysis and management, and including some mathematically oriented analysts and academics.

Audit-l: used by internal and external auditors and linked with the AuditNet website run by Jim Kaplan.

UNCERTAINTY: used by anyone interested in management of risk and uncertainty. Very few respondents came from this source.

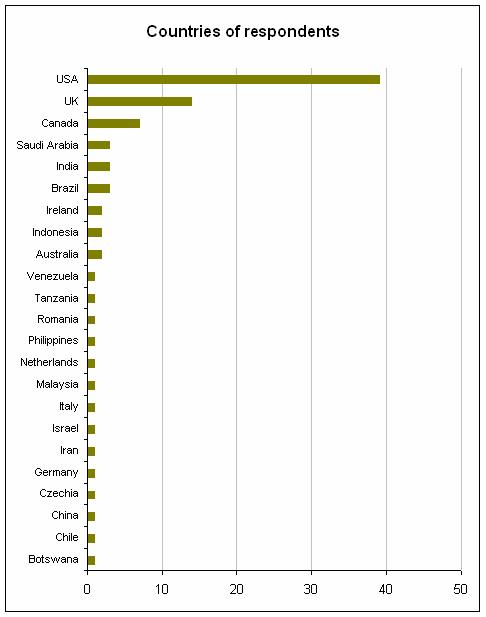

Almost half the respondents were from the United States of America. The countries of respondents are shown on this graph:

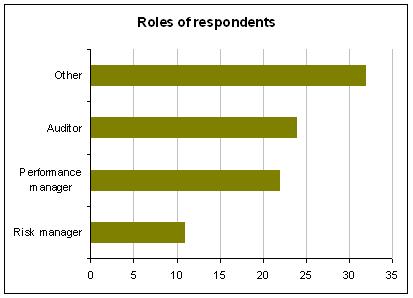

Respondents were asked which most closely matched their background and role.

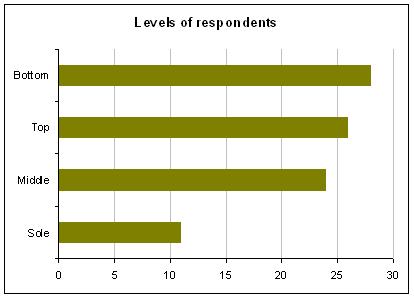

Respondents were asked about their role in their organization. ‘Sole’ indicates someone who works alone or is a student or not employed, and therefore outside an organizational pecking order.

Scenarios and actions used in the survey

Here are the scenarios and actions used in the survey, verbatim, in the order they were presented.

Scenario 1

Imagine you are working in a large company and have been asked to lead a small marketing project to develop a concept for a new product to be used in commercial kitchens. Eight others are in the team you will lead during this initial work and you have called your first meeting for the team. Some of the people in it you know, and some you do not. You anticipate that the project will be tough to do, with internal resistance as well as competition from other companies to worry about. You want to get the project team off to a good start.

Before the meeting, decide on targets for revenue, profit, and initial investment and explain these clearly during the initial meeting.

At some point in the initial meeting, talk about the heights of success that the new product could achieve and the positive impact for the company and the project participants. Encourage the team to think in a positive way and avoid mentioning potential failure or disappointment.

Before the meeting, make some estimates of the most likely revenues, profits, and initial investments and explain these during the initial meeting. Do not be drawn into discussion of other outcomes since this could lead to complacency or unrealistic expectations.

At some point in the initial meeting, talk about the full range of outcomes that might result from the product, from the best to the worst, and various alternatives in between. Highlight the uncertainties at this stage.

Throughout the initial meeting, avoid discussing potential outcomes at all.

Scenario 2

Imagine you have recently started a business of your own, manufacturing wooden toys in a large barn in the country. Your sales force of three people have been selling to shops. To raise money you had to produce a business plan and the plan included estimates for sales of each of the six product lines you currently sell. After several months it is apparent that one of the product lines is doing much better than estimated, two are doing about as expected, and the remaining three are doing worse than expected. You are reviewing performance so far and have to decide what changes, if any, to make in support of each product line.

Investigate the reasons for performance so far, focusing on the causes of under-performance by three of the product lines.

Encourage the sales force to concentrate on improving sales of the product lines that are under-performing against expectations in order to stay on your business plan.

Investigate the reasons for performance so far, focusing on the causes of surprisingly good performance by one of the product lines.

Shift resources away from the disappointing product lines and towards the surprisingly successful one.

Shift resources towards the product lines that are actually contributing most to profitability and sales growth.

Scenario 3

Imagine you are a senior government official who has been put in charge of a high profile building project. So far the building is going according to schedule and the Minister (i.e. the senior politician involved) has taken almost no interest in the project apart from smiling press conference appearances. However, you have recently become aware that the company that is pre-fabricating sections of an elaborate glass roof have hit potentially serious technical difficulties with the design and are in dispute with the architects and construction managers. Angry letters are being exchanged between these three parties and you are being copied in as each positions itself as an innocent party. The true position is unclear. According to your plan there should still be enough time to complete the roof sections and install them on schedule. You have to decide what to tell the Minister, if anything, about the roof situation.

Tell the Minister nothing. The project is still on schedule and there is time to sort out the roof.

Personally visit the roof making company and have them show you the technical issues of which they complain.

Tell the Minister immediately about the dispute and potential consequences, focusing on the worst outcomes. Prepare the Minister for the worst.

Tell the Minister nothing until you have investigated the roof situation and have a course of action to recommend. Then, if your course of action requires Ministerial backing, explain the situation and ask for the decision.

Give the Minister a brief presentation on all areas of risk and uncertainty related to the project, including the roof worries, and covering what you are doing to investigate and manage these, and the potential for Ministerial action or decision making being required.

Scenario 4

Imagine you work in a large bank and have been designing a new form of savings account that you believe could make a big impact in the market and a lot of money for the bank – not to mention giving your career a huge boost. You and your team have developed the idea but you need senior approval to go further. Two days before the crucial meeting at which you must present your idea you discover that another, similar idea has been developed in another department and you see a copy of the presentation about it. You are horrified to see that if the other product is accepted yours will not be so this has become competitive. Also, their presentation makes bold claims about future sales and profits. You know these can be little more than guesswork but somehow you will have to compete with this exciting pitch. You consider your own presentation again.

Do what you can to match or exceed the claims of the rival idea. Carefully remove timid words like 'could' and 'might' and do your best to project total confidence in a successful outcome when you stand up to present.

Do not exaggerate the certainty of your forecasts, and include in your presentation a section on the major uncertainties affecting any product in the sector and the difficulties of reliable forecasting.

Include in your presentation a section on how your plan provides flexibility to respond to different levels of take up by customers.

Keep your presentation short and positive by removing material about contingency planning and research.

During your presentation demonstrate your knowledge and experience by referring to past products introduced by the bank and their various, often surprising successes or failures.

Potential future research and developments

This survey was popular with respondents, who volunteered (and persisted through to the end of the survey) with no incentive other than their desire to help in research and an interest in their own self development. On top of that the survey results have suggested useful insights into how people think about the risk and uncertainty management issues involved and how they might be influenced in favourable directions (though ‘favourable’ remains a matter of choice).

Could surveys like this be used to assess the control environment of an organization? Perhaps. Certainly the scenarios would be more penetrating and convincing than asking senior executives if they think having accurate financial statements is a good idea. An enhanced version of the survey has already been developed with additional scenarios and improved usability.

Could the survey tool be used for educational purposes? I think so and a version of the survey that offers suggested answers and reasons for them is under development.

All these new developments need to be tested to find out how people respond and to study more varied groups of respondents. If you would like to comment or find out more about any of these future developments please contact me at matthew@workinginuncertainty.co.uk.

Related reading

"Open and honest about risk and uncertainty’ discusses the problem of uncertainty suppression, its importance for risk management, and some potential strategies for tackling it.

"Designing intelligent internal control systems’ covers more of the skills and knowledge that help achieve excellent management of risk and uncertainty.

Words © 2006 Matthew Leitch. First published 8 May 2006.