Matthew Leitch, educator, consultant, researcher

Real Economics and sustainability

Psychology and science generally

OTHER MATERIALWorking In Uncertainty

The Lucky Choices Theory of Ability

Contents |

Here, briefly stated, is the Lucky Choices Theory of Ability:

To an extent that is unknown, but could be large, our abilities are determined by lucky choices of technique, not just by genes, teaching, and practice. They reflect the result of many choices we make between alternative techniques, including many choices made with little or no thought. The good news is that we can change our choices and so our abilities, perhaps more than we realise today.

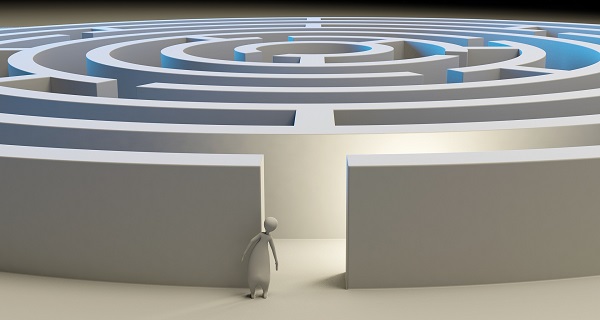

Imagine a complex maze. People who have never seen the maze before enter it, one by one, and try to get to the centre. Each time they reach a junction they must decide which way to go. The maze is complex and unknown so this is no more than a guess. Some choose the best path each time, by accident, and reach the centre quickly. Others make one or more wrong choices, again by accident.

Some people will get through the maze much more quickly than others. What can we deduce about their aptitude for mazes? Not much. Fit, fast runners will have an advantage. People with a good memory for directions will have an advantage because they are less likely to go down the wrong path more than once. However, the luck of those initial choices of route will be the dominant factor.

In this situation it is obvious that lucky choices of method play a huge role, though I suspect many still couldn't stop themselves acting as if some innate talent was involved. In other situations we are not so aware of the role of lucky choices, even though it is considerable. When we see a group of people try something for the first time and some do better than others we know this is not because of practice and infer it must be innate talent. The Lucky Choices Theory of Ability offers another explanation, likely to be true to some extent, which is that the differences reflect lucky choices of technique.

For example:

A child's first attempt at tennis may be their last if things go badly. Yet there are many different ways to hold a tennis racket, different ways to swing it, to move to the ball, to cover a court, to anticipate the flight of the ball, and other things besides. Each of these is like a junction in the maze. The right choice will work better than the wrong choice, and at the start those choices are strongly, sometimes wholly, based on luck.

The results of first attempts at solving a puzzle such as a Sudoku or cryptic crossword will reflect the strategies chosen. The solver might be lucky and try first strategies that work well, or might be unlucky and try strategies that do not work well.

Most skill domains (e.g. tennis, maths, geography, logic, navigation) have many skills within them. Although these skills may have strong similarities (e.g. the various strokes of tennis) there are also differences (e.g. match strategy decisions vs strokes, arithmetic vs algebra) such that to be really successful you need to find more than one effective way of learning, or of acting.

To be very good across a whole domain you need to have something that works well in every area. Unless you work deliberately to learn about, design, and implement effective skills (through trials) that will require getting lucky in lots of different choices.

Sometimes a skill progresses in such a way that later skills build on earlier ones. Each new stage of development involves choices so it is possible for accident to play a role each time.

Often, choices become less accidental and more deliberate as time goes on. Pat Cash (Wimbledon tennis winner in 1987) presumably played tennis first when very young and made his first choices without much thought. As a senior player he reengineered his swing from sideways on to facing forward to help his body and use the new rackets. This was done with the help of a sports scientist and quite consciously. It was also filmed for TV.

Lucky choices influence ability to some extent, and their importance differs from one skill to another. But is this typically a trivial factor that we can usually ignore, or something that is often important and even dominant? Nobody knows at this time, but before you form your own initial view please take a few minutes to consider the finer points of this theory.

How initial choices become more important over time

A number of mechanisms increase the influence of early choices.

Amplification over time

If we do well at something initially we tend to do it more, get more encouragement from others, and get more opportunities to practise and receive coaching from experts. Over time the differences between those who are doing well and those who are not increase.

This seems to confirm our initial theory that we started well because we have natural aptitude, but it does not.

Occasionally we suffer setbacks. The skills that were so effective initially may be unsuitable later on. For example, mathematics changes a lot when children move from arithmetic to algebra, and again when moving from mostly solving problems to mostly writing proofs. Some people find that their rate of progress changes at these crucial stages. Most have resilience, based on previous success, and some skills that transfer positively, and so they find effective strategies to meet the new demands. Some never adapt.

Cumulative advantage

A second reason why lucky choices are so important is that many of our skills build on each other.

For example, the skills used in many basic physical movements and postures (e.g. standing, walking, running) are largely developed at an early age, perhaps influenced by physique and parental example, but also according to arbitrary choices made, usually unconsciously.

A child with good posture is more likely to learn to walk well (i.e. economically, safely, attractively), and more likely to learn to run well. This will be an advantage in all sports that involve running. A good running skill will mean it is easier to run for longer and will lead to more running being done and greater physical fitness.

Here is another reason why a group of beginners, in a sport for example, will perform differently in their first session. Some benefit from more fundamental skills that they already have, whose effectiveness was partly the result of lucky choices.

Some fundamental skills that affect progress in life include posture (affecting athletic skills of all sorts, energy levels, attractiveness, and health), facial expressions (the difference between odd looking and attractive is often just a matter of muscle movements), memory skills of various kinds, reading, arithmetic, and drawing/handwriting.

Learning skills

A third reason that lucky choices have a pervasive influence is that they also contribute to the skills we use for learning. For example:

There are many ways to learn to speak a second language and some work much better than others. As a schoolboy I made a disastrous choice of how to learn foreign languages and as a result failed to make any significant headway despite years of lessons in French and Latin. Happily, when I later started to learn computer languages I used a different strategy and it worked brilliantly.

There are many ways to learn racket sports, and some work much better than others. Exploring the forehand action in a variety of situations, systematically, and building up from slow, low energy motions to full speed and power is just one very helpful approach.

There are many ways to learn to read and some work better than others. Many children learning to read English get stuck for a while trying to use knowledge of the sounds linked to each letter to decode whole words. They can sound out individual letters but do not sound out pairs of letters, or whole phonemes, let alone words. They haven't even realised that putting the sounds together, piece by piece, would help.

Over time, skills of learning that work well in a domain can produce huge improvement, while different learning skills used by someone who is the same in every other way can produce hardly any improvement.

K Anders Ericsson has studied the impact of practice on attainment and shown that a lot of practice is not effective. Only what he calls 'deliberate practice' designed to improve skills makes a big contribution. Without this our skill level tends to stop rising. For a child this means that their apparent gains may be the result of their growth and maturity rather than improved skills.

Lifestyle choices

A fourth mechanism by which lucky choices affect progress is indirect.

A person's daily habits, such as sleeping, eating, exercising, and watching television, and less obvious things like the time spent going over memories of past events, mentally rehearsing future actions, and worrying about relationships will also have an impact on performance.

Many of those habits will also have been chosen by accident, at least partly. They may continue for long periods even if they are unhelpful just because the connection between the habit and performance is not obvious. Many people do not get enough sleep but are unaware of it, and even less aware of what behaviour patterns lead to them having too little sleep.

Limitations on deliberate, guided choices

The initial choice of route in a complex, unknown maze is clearly one that cannot usually be made on the basis of good reasons. We just have to make each choice and try it. We might as well flip a coin each time.

However, in most other skills there are various ways that we could do better than a totally arbitrary choice. The Lucky Choices Theory of Ability proposes that these ways, typically, at present, are less effective than we think and so luck still plays a crucial role.

A corollary of this theory is that there is more scope for improvement than we usually think. We do not have to settle for the choices we make initially and we can make changes, even years after our first choices were made. We can also improve the way we make choices.

Limitations of copying

One important way in which we can do better than flipping a coin is to look at what others do and copy them. Various lines of theory and research suggest that this is an important part of our learning and helps us do better than chance.

However, copying others has some important limitations:

Poor models: Ideally the skills we copy should be high performance skills that will be suitable for us. In practice we often copy the model in front of us, who might be a parent, teacher, peer, or celebrity on television. If your parents have poor posture you may find you grow up with some of the same problems. If all your friends seem to believe passionately in astrology you may find yourself checking your forecast each day, just in case.

Our choice of who to copy is restricted by who is available to be copied but is also another one where lucky choices can make a big difference. If we are deliberate and sensible in our choice we will try to choose someone whose skills are widely acknowledged to be excellent and whose techniques are appropriate for us.

Skills that cannot be seen: The value of copying is limited by the fact that we often cannot see how skilled performers do what they do. If the skill is an intellectual one then we need them to think aloud in some way or their abilities usually remain a mystery. In physical skills the speed of movement may be a problem, with critical parts of a movement performed too quickly to be seen. For example, crucial parts of the swing in golf, tennis serving, and squash drives are too fast to see without slow motion video, and only really clear with super-slow motion video.

If we cannot see the whole skill then we have to fill in the gaps and here again lucky choices come into play.

Details we don't notice: Even if we pick a good model and can see all we need to see there is no guarantee we will notice every detail that is needed for success. Many skills involve getting lots of things right and it is hard to notice everything. We can do better if we are very careful and analytical about it, and if we compare our own performance with the model to discover differences that may signal a point we missed.

More often, we notice only a few technical points so what we notice is another area where lucky choice is involved.

Failure to replicate skills: Knowing facts about a technique does not allow you to perform it. You still need to find a way to act that exhibits the characteristics observed in the model. For example, a fit man of similar build to champion tennis player Roger Federer can spend as long as he likes studying super-slow motion video of Roger playing tennis but that alone will not be enough for an instant technical improvement in the learner's game.

We have to piece our skill together, experimenting to find actions that work as we want them to. What ideas we choose to try drive how successful we are in this, and here again lucky choices are important.

One of the hardest parts of skills to observe and replicate happens to be one of the most important. We need to understand how actions should vary according to the situation. This can involve choosing between different patterns of action and/or varying a pattern to precisely match the situation. For example, consider footwork in the sport of badminton. When you watch top players it is easy to see that they move in various ways. For example, when they need to move forward quickly they sometimes run and sometimes do what is called a chasse, a sort of forward facing shuffle that looks like someone fencing. You might copy the run and the chasse, but not work out how to decide which to use because the rule for this is far from obvious. In addition, even if you copy the basic pattern of the chasse movement that on its own will not allow you to vary the speed and distance covered by your chasses as required in a rally. You need to 'calibrate' your skill so that your actions are adjusted correctly to each situation in a rally.

Some ways to practise skills make it easier to learn calibration, but whether you use them or not depends on another choice that may well be the result of luck.

Limitations of coaching

This includes all forms of teaching and coaching.

In theory coaching should be a powerful and helpful guide to choices about technique and sometimes it is. However there are three important limitations.

A lot of coaching is just setting tasks

Imagine a school teacher sets the class a short essay to write about the Tudor kings and queens. The topic is set, the length, the deadline, the resources to read. The children write their essays and the teacher marks them, gives a grade or perhaps smiley faces and house points, and picks out a few spelling mistakes to be written correctly three times. Very little of this guides the learners in their technical choices. Apart from providing the correct spelling of some words so that they can be written again, the teacher is providing no help, but just setting tasks.

Much sports coaching is similar, with genuine guidance time only a small fraction of the total coaching time. The rest of the time is taken up setting tasks.

Handwriting is an interesting example. Children in the same class at school write in a variety of styles by the time they are 8 years old even though they have had the same teachers, copied the same examples, used the same writing instruments, and sat at the same types of table. Not only does their handwriting look different on the page but the way they produce it also varies. Their styles continue to diverge as they get older.

Teaching styles differ but the main focus is usually on the shapes of the letters to be produced and the paths of the pencil tip as it makes those shapes. There is very little about exactly how to hold the pencil, how to move the hand, how to sit, and how to position the paper. These points make a considerable difference to writing skills but children are left, largely, to choose for themselves.

Some advice that coaches give is poor

Advice given by coaches isn't necessarily correct. Learners have to decide whether to apply advice and here again their choices may be lucky or unlucky. When coaches give poor advice the best performing learners will be those who do not take the advice.

For example, until the mid-1960s swimming coaches believed that swimmers moved forwards by pushing water straight back with their hands and arms. When they gave their learners any advice it was to pull straight back. Then Dr James E Counsilman (later coach to Mark Spitz who won seven gold medals at the 1972 Munich Olympics) used underwater photography to find that good swimmers actually pulled through curved strokes that meant their hands were continually moving sideways into still water. Today coaches teach this style.

Incredibly, in the 1960s a swimmer who did what their coach said would not be successful.

A more recent example comes from squash. In coaching for the sport of squash a traditional piece of advice is to 'get to the T'. The T is a central position on the court. In fact good players almost never try to get to the T. What they do is move to a point near the T but adjusted for the position of their opponent. For example, if they hit a deep drive down the left hand side of the court they will move to a position about a metre back from the T and a little to the left of centre. If they hit a drop they will move forward about as far as the T, while their opponent rushes forward.

The same situation exists in badminton where many people still talk about moving to a fixed 'base' position when in fact top players do not do this, moving instead more like top squash players do.

Learners who, somehow, ignore the traditional advice and use the more effective technique will do better. The effect of the traditional advice is to reduce the number of learners who pick up the best positioning strategies, and to exclude learners who work hardest to follow their coaches' advice.

Sometimes the impact of coaching induces learners to choose particular learning strategies, and these may be poor ones. For example:

I persisted with an ineffective approach to learning foreign languages because my French teachers seemed to be translating word by word. It is more effective to extract meaning from one language then re-express it in the other.

Beginners in racket sports usually start as if each stroke is one movement, not a family, because that's how the sport is taught.

Music teachers waste their pupils' time with 'technical drills' and scales practice. These are not completely useless but there are better ways to spend your time. It is something like teaching touch typing by repeatedly typing the alphabet, forwards and backwards.

For a learner to thrive despite poor advice the learner needs to (1) ignore the advice, and (2) choose effective methods. Both may involve a substantial amount of luck. The alternative explanation is that the learners cleverly work out a better approach and realise the coach has got it wrong, but if it was that easy wouldn't coaches have got it right?

Often coaches do not know how to help

Coaches can find it very difficult to help learners. If the learner is struggling with something then the reasons for that are a puzzle to the learner and often to the coach as well. There is often one thing that is best to change next, but what is it? The learner is probably doing several things wrong but some of those faults are caused by something else and cannot be fixed until the underlying problem is solved.

For example, when I was learning to be a better public speaker I joined the Epsom Speaker's Club, which is a great club for that purpose and part of the Toastmasters network. My persistent fault was to speak for a bit longer than the allowed time of 5 to 7 minutes. "Watch your time!" people would say, "Didn't you see the red light come on?" This well meaning advice did not help because my underlying problem was that I gave speeches more slowly than I rehearsed them. Consequently, I would think I had the right amount of content but run out of time, with no way to shorten my finely worked speech. ("Less content Matthew!" seemed the obvious solution but in fact sticking to speaking opportunities with at least 10 minutes available was much more satisfying and effective.)

If the coach tries to help there is a chance of the advice being on target, but luck again plays a role. The impact of this can be huge.

According to research summarised in chapter 10 of "Nurtureshock" by Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman, parental responses to early attempts at speech by babies are extremely important in language learning. An immediate encouraging response stimulates more babbling. Responding to more advanced babbling stimulates more of it. Saying the name of whatever the child is looking at helps the child learn that name. Saying something else hinders (even if the child seems to be trying to say something else). For babies up to a certain age moving the object while saying its name helps because the movement makes it clear what the baby should be focusing on. A sing song voice helps too. Familiar sentence frames (e.g. "Look at the...") make it easier for the baby to notice the word that is different. Words at the end of an utterance are more easily learned because in the middle it is harder to separate them from other words. Repeating the same message in different words or with different grammar helps establish alternatives, and also teaches different tenses.

At a certain age it is helpful for a baby to focus on shape as an aid to learning concepts. Some don't, but with a few minutes of training, repeated a dozen times, they can be nudged into attending to shape and this helps them learn faster.

These things have only recently been identified by scientists and at least some of the points will come as news to most parents. Tiny differences in behaviour can make big differences to a child's rate of learning and these results were established using experiments with children who, up to the time of the experiment, had not been getting exactly the right help from their parents. When it comes to the tiny differences in parent behaviour that make these big differences to learning, it seems that what parents do with their children is, to an important extent, accidental choice.

The impact of differences in parental behaviour for language development in their children is massive and some of it persists into later life.

Limitations of experimentation

One way to choose between technical alternatives is to try all the likely candidates and see which seem to work best. Even if this is not feasible we can at least keep experimenting with tweaks that might be improvements.

However, we rarely do this to its full extent and there are some genuine challenges that explain this in part:

Combinations: Not only might there be lots of technical alternatives for each choice but there may be many choices involved in a single skill. The number of combinations to be tried out can be huge. Some skills are tougher than others because they require everything to be right before overall success is achieved. Golf is one of the most difficult sports in this respect.

Unreliable feedback: To experiment efficiently you need to be able to assess the impact of a technical choice quickly and reliably. Again, some skills are more difficult than others in this respect and golf is particularly tricky. Where the golf ball goes is an unreliable clue; you can hit a great shot by accident and a poor one with a swing that was 99% good.

Alternative evaluations: How do you judge if one method is better than another? It depends on how you define 'better'. What do you pay attention to, and perhaps even measure and record? What direction of change is an improvement. Should you be focusing on speed, or accuracy, or strain, or control, or economy, or something else entirely? What we attend to and what we define as an improvement or a success drives what we learn. Some choices are better than others. Choosing how to evaluate alternatives is yet another opportunity for luck to play a part.

The moat effect: When you change something about your skill the immediate result is often that you perform worse than before, even if your change was a good one that has the potential to give huge gains. This is called the moat effect because, as you approach the peak of performance there is a drop in performance, like dropping down into a moat before you can climb a castle wall. Technical details are rarely separable. A technique that is fundamentally flawed but finely honed may perform better than a technique that is fundamentally superior but ineptly executed.

Even if we experiment energetically to find skills that work better than our first choices this still does not fully remove the impact of luck. The first new thing you try might be a huge improvement, or the first ten things you try might be useless. It may take a very long time to find skills that really work well, when there are many alternatives, which is often the case. This search can be shortened somewhat by carefully observing the skills of experts (e.g. using slow motion film of sportspeople) or taking advice from a coach.

However, in most cases people do not experiment with alternatives or look for guidance from experts to anything like the extent that is possible and would be helpful. We don't realise how much difference it could make and instead we just assume that we aren't very good at something and live with what we have.

Strategies for success

If the Lucky Choices Theory of Ability is true to any significant extent then there should be strategies that help us. For example:

Deliberately experimenting with alternative skills, trying to learn from observing experts, and getting good advice from coaches should all help to a large extent, especially if early progress is poor.

We may need to dig deep and fix tiny details, including some skills we first acquired many years before.

Traditional coaching advice that is poor should be searched for and eliminated by people responsible for improving teaching/coaching.

This applies to the skills of learning too.

We should see our abilities (including our 'cleverness' or 'intelligence') as easier to change than we have assumed in the past and be prepared to try more things in an effort to get better. If at first we don't succeed it is not necessarily because we lack talent. It may be just that we haven't found the easy path through the maze yet and need to keep looking. Once we find the right path we may be able to progress as quickly as anyone else.

Made in England